BEHIND THE BOOK: THE SISTERS OF SUMMIT AVENUE

The Indiana School for Feeble-Minded Children

I grew up down the street from the Indiana School for Feeble-Minded Children in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Children were warned to stay away from what we called the “State School” but those of us kids who lived close enough couldn’t avoid hearing and seeing the horrors inside. Yes, it was terrifying but it was also confusing. Here were humans suffering, and we were not supposed to help them? We were told only to stay away.

I never processed this growing up–it was just the way it was. But it might explain why, in 1982, on a visit to my parents’ house, when I saw the State School being torn down, against all reason I rushed to get onto the ruins.

With my baby Megan strapped in her carrier on my back, I picked my way over the rubble. Only a few shaggy walls of the hospital building were left. And then I saw it, tilted on the debris: A white iron baby crib. Thick leather straps hung, flaccid as dead snakes, from its bottom. Here was the proof of all I knew and didn’t want to know. Even as I broke down, panic-stricken, nauseous, breathless, sobbing, I knew that this was one of the most important moments of my life.

Thirty-some years later, that iron crib became the catalyst for me to write The Sisters of Summit Avenue. My heart will never heal from the sight of that crib, nor should it.

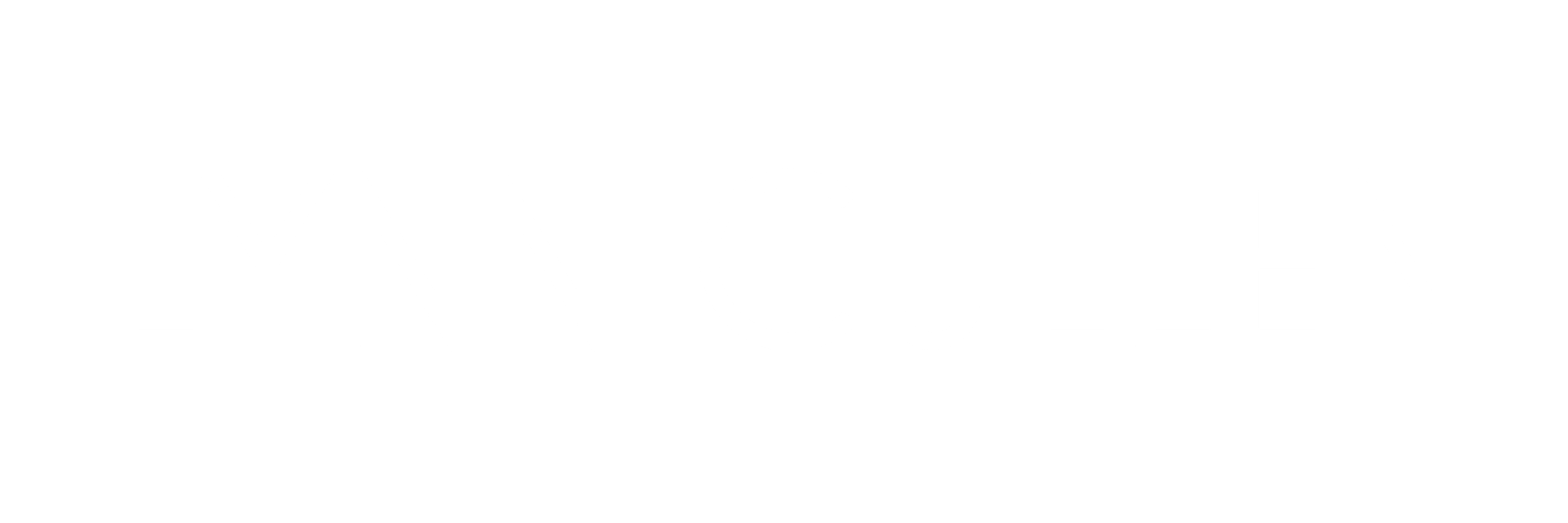

An Early Better Crocker Cookbook

Before the famous red cookbook beloved by so many of us and our mothers, Betty Crocker turned out little publications like these. The ladies in The Sisters of Summit Avenue worked on this one in 1933. Don’t think it would fly today…

The Dust Storm of 1934

Chicago, May 9, 1934: the day a black blizzard swept across the United States. Starting on the Plains, and dumping into the Atlantic, no part of the country east of it was spared—definitely not the farm where the dysfunctional Dowdy family was having a showdown in The Sisters of Summit Avenue.

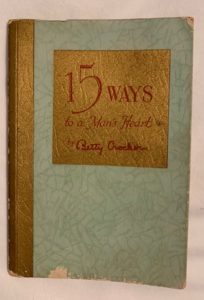

“We Doughtys Tried to Cook Up Something New”

My dad, Bill Doughty, made a Christmas card every year, hence “the same old dish” line in the card here. Every year he thought of a new way to celebrate what it was like to be a Doughty (which was just ordinary middle-class American, but that didn’t dim his pride.) He told a story in pictures of his deep appreciation for his riches, which he always measured in family.

It has occurred to me that I’m doing something similar with The Sisters of Summit Avenue. A departure from my previous books because it centers around a fictitious family instead of a historical figure, (although there’s plenty of Depression-era history in it,) I call it my It’s a Wonderful Life. The sisters in the book stand to lose the treasures that they have because they pine for what they don’t have. They must learn what it means to be truly rich. But Bill Doughty knew, all along.

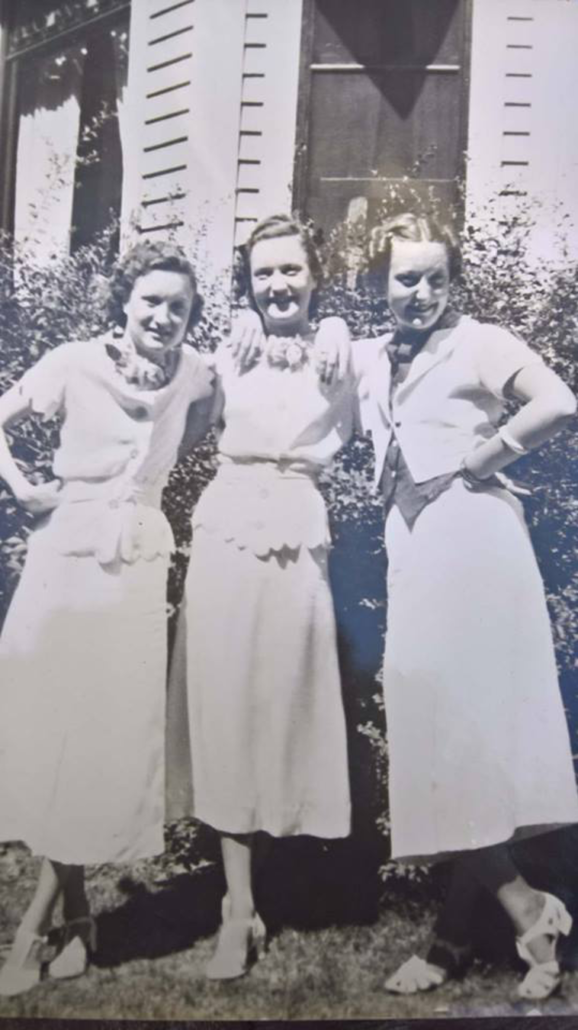

This Wonderful Life

The fab three pictured here are my mother and her sisters in 1934, the year in which my novel The Sisters of Summit Avenue opens. My mother was part of the Singing Kiess Sisters, radio stars in their corner of the Midwest. My mom, the vivacious one in the middle, played trombone.

I wish I had known her then. The truth is, I hardly knew her at all. By the time I was born, she was mired in the swamp of mental disorders that would consume her for the rest of her life.

She is gone now. In an effort to imagine her before she was ill, I have been sifting through my childhood memories, and through the stories she had told me of her youth. I picture her as a spunky farm-girl—she rode a cow on a dare. I imagine her as a young woman with hopes and heartaches and dreams, and as a young mother surviving those worst of times, yet those best of times, with small children.

The Sisters of Summit Avenue grew from these imaginings. I ended up telling a story in which fictitious characters do fictitious things. It’s a novelist’s sort of memoir—real-life incidents have been spun into something else entirely. But the way in which the mother’s grown daughters misunderstand her because they can only see her through their own experiences comes straight from my own life, undiluted by fictionalization. You are shown Dorothy and her daughters through the lens of my personal regret.

In The Sisters of Summit Avenue, the two sisters and their mother are in danger of losing the good things that they actually have by always pining for what they don’t have. I was guilty of this with my mother. How I wished for her to be a perfect mother and homemaker, a hostess worthy of Betty Crocker. Couldn’t she be just “like everyone else”?

In Sisters, the daughters and their mother have a shot at second chances in their lives. I believe that change and redemption are possible for those who seek it, so I give my characters a crack at it. They still have an opportunity to right their wrongs. The opportunity is there for all of us. As Dorothy, the mother in the story, says in her unadorned way, “You’re not dead yet.”

I wish that I’d tried harder to appreciate my mother when I had her, as quirky and sometimes as difficult as she was. I wish that I’d appreciated that spunky girl inside her. But writing The Sisters of Summit Avenue has opened me to thinking about the child, the young mother, the life-scarred woman-who-was. I’m closer now to finding that perky young woman with the big trombone. Little did she know as she crooned on the radio with her sisters that she would someday have children, and grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, all of us owing our chance at this wonderful life…to her.