Scholarly debate still rages as to why he was found, four days before his death, delirious and in borrowed clothes, in Baltimore, Maryland, far from his home in New York City. Theories as to the cause of his demise range from alcoholism to rabies. (I personally throw my lot with meningitis.)

If the death of America’s most instantly recognizable poet remains enigmatic, what about his life? How much do we really know about Poe? Was he the chillingly murderous madman of so many of his tales, as well as a spectacular drunk? If not, who was he?

These very questions drove me to write my novel, “MRS. POE” (Gallery Books/Simon & Schuster.) To understand Poe, I slipped back in time to 1845 New York City, the year and place that he wrote his most famous poem, “The Raven.” To get there, I burrowed into library archives, walked Poe’s streets, and pored through his work. My research uncovered a startling possibility: That critical year, four years before his untimely death, Poe fell in love. And not, it seems, with his wife.

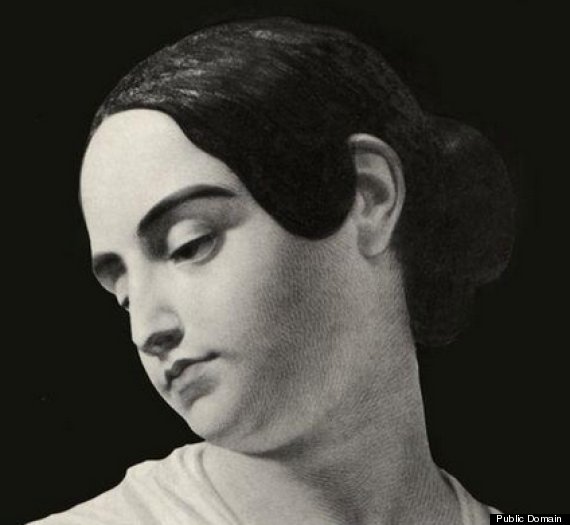

The mystery woman was Frances Osgood, a poet known for her children’s verse and flowery poems. When she met Poe, she had recently been abandoned by her husband and was trying to scratch out a living through her writing. The pair obviously hit it off–soon they began to publicly exchange anonymous love poems. That summer, he courted her past midnight at the home of mutual friends–just down the street from Poe’s own home, in which stewed his upset and anxious wife. The pair couldn’t keep their eyes off each other at parties. People noticed, among them Frances’s disgruntled would-be suitors. But no one watched the couple more closely than the Reverend Rufus Wilmot Griswold.

Already Griswold and Poe were enemies. Poe had slammed Griswold’s poetry collections and had further enflamed his rival by encroaching on Griswold’s turf in literary criticism. Now Poe had won the woman Griswold coveted. This meant war.

Griswold’s potshots at his opponent did limited damage while Poe was alive–everyone knew Griswold was a hotheaded crank. Only after Poe died could Griswold wreak his revenge, but it was worth the wait. In one of the most bizarre turns in literary history, Poe’s aunt and mother-in-law, Maria Clemm, made Griswold the executor of Poe’s papers–a strange move, considering Griswold’s widely-published malicious obituary of the man. Once his rival’s papers were in his hands, Griswold set about doctoring Poe’s letters, spreading lies about Poe’s behavior, and concocting a biography chockfull of inventive slander–a biography which would stand alone for the next 25 years. Even subsequent chroniclers used it as the cornerstone of their view of Poe.

Soon Griswold’s trash-talk had firmly embedded itself into the public imagination. But in yet another twist worthy of a Poe tale, Griswold’s smear campaign backfired. It turns out that people liked the black legend of Poe. As completely false as it is, we still nurture it to this day. So who is the man who wrote “The Raven” and the many chilling tales that are etched upon the American consciousness? As I make clear in “MRS. POE,” he is not who we think. Come peer with me now behind the velvet curtain of time for a glimpse of the real Edgar Allan Poe.

1. The ladies loved him. Women fought to have him come to their parties and swooned when he read his poems. One woman thought she’d clear her way to Poe’s heart by blowing the whistle on his affair with the married Frances Osgood–a particularly ineffective way to get your man.

2. “The Raven” made him a star. Almost overnight, Americans were chanting the catchword ‘nevermore.” Parodies popped up in newspapers across the country and kids followed him down the street, flapping their arms.

3. He was a cat fancier. In spite of his tale about the murdered black feline, Poe loved cats and they loved him. His devoted tortoiseshell, Caterina, went into a depression whenever Poe traveled. Upon his death, their psychic tie was broken. She died two weeks later.

4. He couldn’t afford to pay the rent. He cleared around $400 in 1845, the year of “The Raven”–a banner year for his wallet. Most years he made far less, forcing him to constantly beg friends and family for “loans.”

5. He was a looker. Forget the images of baggy-eyed lunatic so familiar to us all. They were taken in the year of his death, when he was ill, never a good time for one’s close-up. His portraits from the time of “The Raven” depict a dapper and handsome ladies’ man. Said one admirer, “Gentleman was written all over him.”

6. He was as athletic as he was handsome. Besides holding a record for swimming six miles up the tidal James River in Virginia, he enjoyed rowing around Turtle Bay in New York City and hiking through the countryside. He was a champion long jumper, bursting his only pair of shoes during a contest. He won.

7. He went from champ to chump within the space of a year. The success of “The Raven” made him the toast of the New York literati in February 1845. By February 1846, the same literary circles had shown him the exit after they could no longer ignore his attachment to Frances Osgood. Osgood saved her reputation by denying the relationship and reuniting, even though pregnant, with her estranged husband. Poe, on the other hand, sent her a valentine to be read at a party from which he’d been banned. Not a good way to plead one’s innocence.

8. He clutched during the biggest event of his life. Born in Boston, Poe dreamed of coming back and taking the town by storm. He got his chance the year of ‘The Raven’, when he was asked to present at the Lyceum. To a packed house, he delivered a lame poem he had written as a youth. Not even its spiffy new name, “The Messenger Star,” could redeem it. The Bostonians were not amused.

9. He robbed the family cradle under duress. When Poe’s rich cousin, Neilson Poe, bid another of Poe’s cousins, 13 year-old Virginia Clemm, to come stay in his plush Baltimore mansion, Edgar panicked. He had recently lived with Virginia and her mother and now thought of their poverty-stricken home as his own. To keep Virginia from running off to Neilson, Edgar, 26, and still suffering from an orphan’s fear of being abandoned, offered her his only asset: himself. The resulting marriage between first cousins was thought to have been more brotherly than romantic. Some modern scholars doubt if it was ever consummated.

10. He attended his local book club. In 1845, literary fan Anne Charlotte Lynch invited writers and other artists to her New York City home to discuss books and ideas. She kept it casual, unlike other hostesses, offering only tea and Italian ices for refreshment and insisting that guests dress informally. The guests entertained themselves with their discussion. Lynch’s Saturday night “conversazione” was a hit. Poe went often–until the Frances Osgood scandal got him promptly uninvited.

11. He had bad PR. The image of the hard-drinking drug addict that we know today comes to us courtesy of Poe’s archrival, Rufus Griswold. In reality, Poe’s strict work ethic allowed him little time to drink. The small dose of an opiate that he took once for an illness made him so sick that he swore it off for life. But destroying Poe’s reputation didn’t bring Griswold happiness. He spent his final illness alone in a room hung with three portraits: His own, Frances Osgood’s, and Poe’s.